The "Rebirth" of Japanese Studies: Round 1 Responses

This page compiles the first round of responses to the Association for Asian Studies virtual roundtable, The “Rebirth” of Japanese Studies. Participants responded to statements by four discussants and the roundtable chair on the current state and future of the Japanese Studies field.

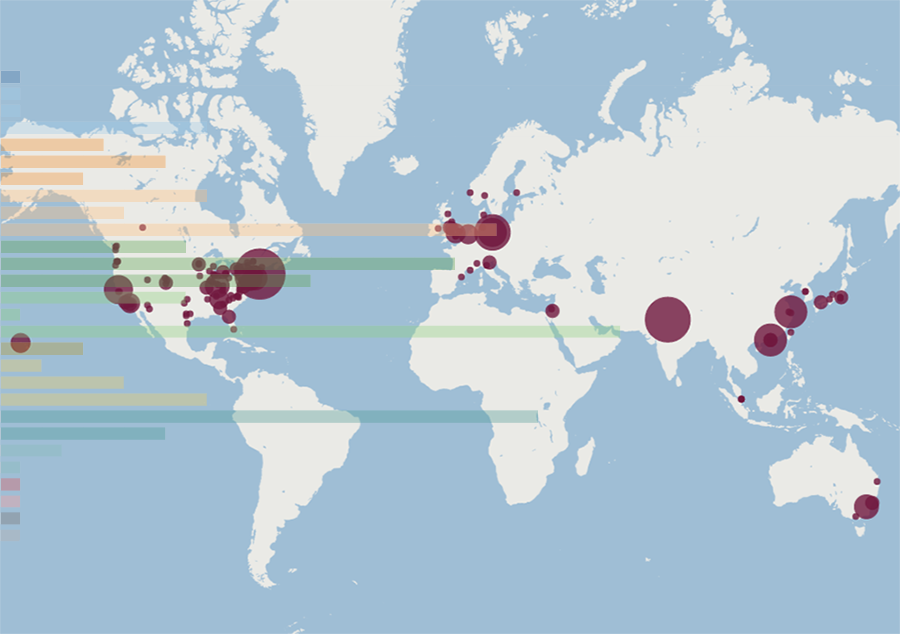

There were 19 submissions from a diverse array of Japanese Studies specialists in Round 1 (May 1-14, 2020). In addition to the original discussant statements and the 2019-2020 job market data, I encourage readers to carefully read the comments below.

Links have been added to some comments below for easier navigation to resources mentioned or specific discussant statements, and responses have been grouped roughly thematically. Click a name in the list to jump to an individual of interest or simply scroll down to begin reading in the order provided.

We sincerely thank those who contributed in the first roundtable response period and hope that readers will also read responses in Round 2 and Round 3. Please contact me via email with any questions.

Bates College, Lewiston, Maine, United States I am a second-year TT assistant professor of Japanese at a very small liberal arts college, where I teach both language and culture courses. One issue that has concerned me between the time I left graduate school (2018) and now is whether Ivy League and R1 grad programs are preparing PhD students for the broad market that exists rather than purely as potential R1 professors. Hierarchical and even dismissive attitudes toward generalist, 100-level, or language teaching duties (even teaching in general as opposed to research) exist in the field, and I believe it is very dangerous for senior scholars, mentors, and advisors to pass these ideas along considering the shape of today's job market. I was lucky to land an excellent-fit tenure-track job my first cycle on the market, where I have been extremely happy, and see a future for myself. Besides good fortune, I believe it helped quite a bit that I had language teaching experience as part of my program, and that I did coursework in Second Language Acquisition during grad school even though I did not expect language teaching to be a large part of my future duties. Yet, I have heard of graduate students at Ivy League universities doing less and less language teaching (for various reasons, including but not limited to disputes about the treatment of graduate student labor and increasing pressures from administration to reduce time-to-degree in fields like ours, which have a higher average time to PhD completion than others). At many prominent institutions, language teaching is completely siloed off from literature teaching in departmental structure. But in small institutions and institutions where language, literature, and area-studies faculty are being re-arranged and often combined, smaller faculty sizes mean increased demand for those who can fill multiple functions. Language teaching is a key piece of the puzzle. I believe that neglecting language teaching training for graduate students in Asian literatures, cultures, history, film, anthropology, etc. runs the risk of locking away a significant sector of job opportunities for PhD graduates, which is tremendously worrisome. Once a PhD student graduates, finding opportunities to get starting language teaching training and experience is extremely challenging. No matter how stellar a graduate's research, if the post requires language teaching, that typically is not negotiable, especially in small departments. It is essential that mentors and advisors prepare graduate students for the market that exists today, rather than the market that may have existed at other points in time. I believe (in agreement with others in this roundtable) that the current market demands diversified skills, and even brilliant students may need to be pushed beyond their narrow focuses. In my personal opinion, it would also be extremely helpful if we could all work to resist hierarchical attitudes in the discipline that automatically exalt high-volume research while denigrating language teaching and, in the worst cases, dedication to teaching in general. As a grad student, I had only limited awareness of what jobs at various institutions might look like, and did not realize fully that many of the attitudes and much of the advice I encountered was very specific to reproducing one specific type of career amid many equally valid options. (Here I echo observations by Landeck and Pendleton.) I was lucky as a graduate student that some language teaching faculty took their mentorship of me seriously, and pushed me towards serious and thoughtful language pedagogy. Teaching language has made me a better researcher just as teaching classes on literature and film has. Resisting narrow views of what constitutes value in the field may also help mentors, advisors, and senior scholars to cultivate broader and more diverse professional networks, creating more possibilities for guiding the next generation of scholars.

Salisbury University, Maryland, United States I have many (unfocused) questions about the broader epistemological concerns behind area studies, but I want to focus my comments here on some commonalities my experience shares with Laura Miller's and Melinda Landeck's contributions. I, too, think that Japanese studies PhDs are not adequately prepared to be faculty at anywhere other than R1 institutions. From anecdotal evidence, I think the Ivy Leagues actually prepare their PhDs for the job market and their careers less adequately than larger state R1s. Unlike Prof. Landeck, I am at a mid-size state comprehensive university, but some of my challenges and adaptations have been similar to hers and to the issues Prof. Miller raised. First, we need to be able to teach broadly and enjoy teaching broadly. I am the only East Asianist at my university, so I take the additional burden of teaching all Chinese history courses as well as Japanese. Out of a sense of obligation to my students, some of whom may go on to graduate school, I feel I need to give them as up-to-date and comprehensive an introduction to Chinese history as I can. But since pre-modern Japan is my field, I have to do extra work in reading and preparation for my China courses and retool them more frequently. Making things outside our field interesting and exciting for our students as well as us is critical, but I think that process should begin in graduate school--TAing outside our specific fields, having required external orals fields, etc. I took seminars on China and Korea and did an orals field on pre-modern China but that was largely out of my own initiative. Even just envisioning yourself teaching broadly can help you in the academic market--I have seen candidates unable to move onto the campus interview phase because they did not express interest in teaching broadly or only seemed excited about courses very specific to their interests. Second, the balance of teaching, research, and service is different at each institution and many liberal arts/state schools focus a heavier burden on teaching and service than research. However, this does not mean research is insignificant or optional. One of the pieces of advice I received that was unhelpful is that I should not worry about submitting articles in my ABD/early job market phase--a dissertation from an Ivy League is enough to get a good job. Unfortunately, if this advice was ever true, it is no longer true in the buyer's market that is the post-2008 recession. After serving on a search committee, I saw that even at my institution (where research is not the most important criteria for tenure), a candidate's research profile played a role in who was admitted to the conference interview stage. Should we encourage new PhDs to take a year-long break from their dissertation revision and submit an article before going back to the book project, especially if they are aiming for employment outside of R1 institutions? Finally, course enrollment numbers are the "currency" of value for many institutions and I agree with Prof. Miller that we need to think about teaching courses that have broad appeal. I noticed an uptick in my success rate at getting interviews when my job materials started mentioning transnational, comparative, or other broader course ideas. We are often told teaching is a chance to put in place your "dream course" but if your dream course doesn't have appeal, there could be real consequences. Again, thinking about this at the grad school level would be helpful. I could imagine one solution to these graduate training problems could be a system of mentorship where R1 advisors (who often don't know much about places outside of R1s) could be in touch with former cohorts who found employment at other institutions and have them give pointers or bring them back to give advice to new PhDs. However, the job market is competitive and we need to be keenly aware of the ethics of it. Should we be supporting a wide range of candidates to receive gainful employment instead of allowing a few institutions to created ironclad pipelines from PhD to professorships? Do we owe anything to our institutions of training, or are strengthening those connections a kind of tribalism? How do we balance obligations to our field, our former institutions, our colleagues, our students, and other allies in our new places of work? And how can we envision a kind of humanities-based solidarity that can push back against the greatest problem of all: the commodification of education in our neoliberal atmosphere where administrators, students, and legislators are all pushing professors to justify the "value" of what they teach, instead of embracing the potential that deep investigation of the human world can have for lifelong learning, multiple careers, ethical development, engaged citizenship, and social justice?

Assistant Professor of Japanese at the University of Calgary, Canada I was glad to read this collection of thought-provoking essays. One aspect that stood out to me was the discussion in several pieces on the job market and recent moves from a tight disciplinary focus to jobs, courses, and degrees structured more broadly around transnational or pan-East Asian concerns. Certainly, in Alberta, Canada, where I teach, we have already seen this tendency in the form of amalgamated language departments and majors that bring together colleagues teaching Japanese, French, and the indigenous language Blackfoot under the same departmental roof. There are some undeniable benefits to this sort of cross-collaboration. There are also challenges. It strikes me that while the language of administrators, department heads, and job ads may increasingly reinforce this broad conception of our field, the actuality of Japanese studies remains several steps behind. And this rigidity when it comes to discipline and scholarship directly impacts graduate students and junior colleagues seeking to work in these broader areas. For me, as an Assistant Professor of Japanese popular culture at a Canadian research institution, this is most visible in the treatment of manga, anime, and game studies within our field. I’m struck by the ways in which manga and anime studies are often championed in terms of student enrollment numbers and interest from a departmental standpoint. We should, the argument goes, all put a little bit of Pikachu into our classes. Yet, there remain very few full-time academic positions advertised for young scholars who engage in this work, and those jobs that do appear typically hire people with a more established backgrounds in literary or film studies, though not exclusively. Meanwhile, our graduate students in Japanese studies continue to write dissertation projects on trendy and timely topics such as Memorable Cats from Japanese Sci-Fi Anime, but there remains a tangible concern about where to publish this work post degree. Manga and anime projects can often fall into the cracks in Social Science and Humanities research funding if not properly defined (are they visual and media studies? Are they literature?). To be sure, there are a handful of journals specializing in East Asian popular culture, but most of our field’s top-tier journals remain somewhat conservative in the types of manuscripts they accept. This leads to concerns about publishing enough so as to not “perish” in the tenure process, and, more generally, about communicating the value of one's work on the popular to colleagues and admins particularly in these aforementioned amalgamated departments. I think if we are to see a “rebirth” of Japanese studies we would do well to align graduate education, hiring, publishing, and promotion and tenure around these new areas of concern. Or at least be honest about the disjunctures that exist in this chain. Otherwise, we are only really supporting this scholarship at face-value and our field remains one foot in the past.

Rural Midwest, United States Melinda’s experiences mirror mine in some ways. It has been difficult for me to sit down and formulate a response to this panel for many reasons that I think are worth highlighting as a part of this discussion: 1) Grades are due today. 2) Tomorrow is the deadline for redesigns of our college website. I am in charge of the History and Asian Studies webpages. 3) While this has been percolating for a while, a couple weeks ago it was announced that the College needs to make significant financial cuts over the next three years and a “Restructuring and Redesign” committee has been put into place. The school needs to make deep cuts to faculty that will likely include tenure-track junior faculty (and possibly even tenured ones). We’ve been asked to do “thought exercises” about cutting a faculty member from every department, and I am a junior member in a three-person department – and one could argue that the other untenured faculty member who is the only US historian would contribute “more significantly” than an Asianist to a history program in an American institution. 4) All of the above cuts – even if my job remains – will likely get rid of all of the contingent faculty who have been contributing to the Asian Studies minor. That minor (which I created) will thus likely go away for the foreseeable future. 5) How do I redesign the websites if I don’t even know if these departments/programs/my job will exist in a year? What are the ethical ramifications of promoting these programs to potential students? Like many of us, I’m not really in a good mental place to sit down and contribute meaningfully to this conversation, because it will probably come out more bitter than I mean it to be. So many of us need help from those in more secure positions to see the field succeed, because right now, we’re just trying to survive this moment.

North American Coordinating Council on Japanese Library Resources / Yale University, United States Even though we are confronted with the idea of a "death" of Japanese studies, Japan Studies librarians in North America have been tirelessly working to expand and improve access to information and Japanese research materials beyond institutional limitations and national boundaries. By providing easier access to the scholarly information necessary for all the various disciplines within Japan Studies, librarians are optimistic that our efforts will contribute to a “rebirth” of Japanese Studies. Many of these efforts are collaboratively coordinated through organizations like the North American Coordinating Council on Japanese Library Resources (NCC) and the Committee of Japanese Materials (CJM), a subcommittee of the Council on East Asian Libraries (CEAL). With the recent challenges due to the coronavirus pandemic, scholars' options for accessing information have shifted dramatically and almost exclusively to remotely accessible resources. To adapt to these changes, NCC committees like the Digital Resource Committee has been working to increase access to ebooks and online journals of academic publications on Japan. Also, members of the NCC Comprehensive Digitization and Discoverability Program task force have been working to develop effective ways to bring to light hidden, academically useful Japan-related materials through digitization, to enable more robust use of these items through institutional collaborations, and to build an international infrastructure for digitized materials. However, it is also becoming glaringly apparent that the rise in the number of available e-resource subscriptions has widened the discrepancy of information available to the haves and have nots. For example, an independent scholar, who may not have access to institutionally available library resources would previously have been able to access physical library materials via Interlibrary-loan. This access has become much more difficult to achieve via access-controlled e-resources. To address this challenge, NCC's Outreach Working Group is coming up with ways to support faculty researchers and independent scholars of Japan, particularly those who are affiliated with small institutions or are otherwise without access to comprehensive Japanese library resources. As the current chair of NCC, I would like to introduce many other NCC essential committees and working groups like the Image Use Protocol Working Group, the Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery Committee, and many more. These groups also strive to provide various services that benefit scholars, teachers, and students of Japanese studies directly and indirectly. However, the work necessary for these committees to accomplish their many tasks is time-consuming and never-ending. Moreover, the time librarians have to commit to these committees is limited by their various duties and responsibilities at their own institutions. We often need more human resources to contribute to these multiple projects, but more importantly, we are eager to gather feedback and contributions from those scholars who we are serving. As Dr. Patricia Steinhoff, Professor Emeritus in Sociology at the University of Hawaii, discusses in NCC’s most recent interview in our ongoing Multimedia History Project series, Japan Studies fields and the materials needed to conduct research in them is constantly evolving. In this sense, the "rebirth" of Japanese studies for the library fields means to keep meeting new needs, as they arise, and enhancing ways of accessing information for those who are passionate about advancing the scholarship of Japanese studies and related fields. We do this by increasing communication and collaboration, not only among librarians but also with scholars, teachers, and students from institutions and organizations across North America and beyond. If you would like to become part of this process, please sign up to become a member of NCC and contribute your ideas and energies to the rebirth of Japan Studies.

Japanese Studies Librarian (Assistant University Librarian), University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States My response addresses points made by the discussants about the way in which doctoral programs prepare students for careers, the advocacy work we need to do within our universities to prove the worth of Japanese Studies, and the need to expand one’s teaching abilities beyond one’s immediate area of research expertise and doctoral training. These comments are based on my current experience as the Japanese Studies Librarian at the University of Southern California (USC), a private R1 university, as well as my previous experience navigating the job market for positions in libraries and academic departments at universities in Australia and the U.S. My PhD is from the University of Sydney (Australia). I was previously a VAP in East Asian History at UC Santa Cruz and Postdoctoral Fellow in Japanese Studies at Stanford. Melinda Landeck discussed “the ways in which largely R1 doctoral programs can better prepare new PhDs for the changing landscape of the Japanese Studies job market.” Her discussion resonated with me. In my case, the job I currently have was not even one I knew existed at the time I was doing a PhD (subject specialist librarian positions not really existing in Australia in the same way they do in the U.S.). There are many skills from my PhD which helped me land my current job and which allow me to succeed in it but it would be wrong to say my doctoral program prepared me for this job in any direct sense. I spent several years inside and outside academia on a circuitous path which eventually led me to this position. How can graduate students who want to explore “alternative careers” other than the TT Assistant Prof at an R1 “standard” be better prepared? How can we address the lack of preparation for “alternative careers” at an institutional level and individually (I am using the term loosely because while many people see librarianship as an alt-ac career I do not, given that in my case I am tenure-track faculty at an R1 with access to research funding)? Individually I think a good option is to seek out mentors who have a job that interests you, be it teaching at a SLAC, working as a librarian, or anything else. For me this was a critical step - while a postdoc at Stanford I connected with Dr. Regan Murphy Kao, the Japanese Studies Librarian there. I not only realized this was a job that existed, but that it interested me and based on my skillset I might have a shot at it. I received excellent mentoring and career advice from her and try to return that favor now whenever graduate students reach out to me for career advice. Institutionally, I think we could develop alternatives to traditional TAships within the department which help prepare students for a multiplicity of career options. For example, could partnerships be formed with SLACs in the same geographic area to give students at an R1 exposure to teaching in that environment, or to work with individually tutoring and mentoring undergraduate students writing theses? Could students work in the library at their R1 for a semester, perhaps on a special project such as developing a distinct collection, writing a research guide, developing information literacy course plans, or a digital project to interpret and contextualize a (set of) primary sources the library holds (ie: not working as a student worker shelving books or on a circulation desk but doing something more in-depth and specialized)? Such partnerships would have to be developed in a way that is win-win for both partners, and beneficial for the student’s career goals (and be properly remunerated!). Even if a student never got a job at a SLAC or as a librarian, exposure to different types of work within the academy that use and develop their skills as a teacher, or a researcher, or interpreter of information would ultimately be beneficial. And if they do apply at a SLAC or a library they will be better positioned for having had relevant experience. Laura Miller discussed advocacy to prove “to fellow faculty members, administrators, and students why we need Japan Studies.” This is true in the library as well. We have to advocate for why we need to buy books and e-resources in a language only some people on campus can read. Current COVID-19 related budget cuts may mean a decline in funding as usage statistics for books and e-resources get scrutinized more closely. I urge those who are at institutions with Japanese collections in their libraries to advocate for library resources, working with their librarian, at the same time as advocating for their programs. And use the collections that your library does have as much as you can. Work with your librarian to develop classes using library resources, for example Japanese rare books can be introduced in literature or art history classes. Japanese newspaper databases can form the basis for an assignment for advanced language students. For those not at institutions with Japanese collections or specialist Japanese Studies Librarians, reach out to the NCC Outreach Working Group. Finally, Miller, Landeck, and Takeshi Watanabe all made references to the need to expand one’s teaching abilities beyond one’s area of research expertise. I often describe being a librarian as being a generalist. In one week I can be working on a digital project with Edo period books, advising a graduate student researching contemporary Japanese photography, planning a conference on Alice in Wonderland in Japan, and doing my research as a historian of Edo and Meiji period Japanese tea culture. I think having trained in an interdisciplinary department of Japanese Studies, rather than in a history department, has helped me make this transition but it has taken time to step outside of my comfort zone. No matter what job we have within Japanese Studies, being able to work outside of your specialization is becoming increasingly important and something I agree we should embrace rather than fear.

R1 Private University, United States As the number of jobs for historians of Japan shrinks around North America, it poses a tough choice for many younger scholars and recent ABDs on the market: continue to pursue the dream of a faculty position, or transition to alt-ac careers. Most critically, both will require a significant "move" -- either geographically or professionally. This was the conundrum I found myself in on the market this year, and I suspect I was not alone. I had two choices. If I wished to pursue a faculty position in Japanese history, I determined it would be most pragmatic to look into job markets outside North America. Of course, this poses enormous challenges and obstacles, the least of which is navigating an entirely new market, along with local working and living conditions. Needless to say, this also necessitates a level of personal and family mobility inaccessible to many. Alternatively, if I wanted to prioritize location, then it would mean giving up the dream of that coveted Tenure-Track job and pursuing a new alt-ac or academic-adjacent career. I don't mean to suggest that these non-faculty jobs are any less fulfilling than a traditional faculty position, and I wholeheartedly agree with those who would encourage us to redefine standards of "success" and "contribution" in the field. Nonetheless, it can be a daunting prospect for somebody who spent years training for one career to suddenly transition to a new one -- luckily the number of resources in this regard has increased as more scholars have opted to pursue this route. Still, with increasing specialization and new certifications required for many alt-ac jobs commonly open to historians, we shouldn't assume a quick or easy transition simply because we hold a PhD. Neither choice is an easy one to make. So, what is to be done in an environment of dwindling academic job markets? Individual scholars currently on the market must make the tough choices that work best for them personally, professionally, and for their families. Until there is a sustained upswing in Japanese history jobs, the market will continue to force scholars into this Faustian bargain. Moving forward, if departments are truly invested in their PhD students' professional success, they must make professional training and alt-ac career training a core component of their graduate programs and better prepare students for the possibility of careers outside the tenure-track. This, of course, presents more obstacles and existential dilemmas for departments to tackle. But maybe this will force those in secure positions to begin to feel the sense of crisis those of us contingent faculty members have long felt, and foster alliances that will lead to positive change in the field and the market. TLDR: job seekers have to be open to change either in terms of geography or job; departments must prepare PhD students for alt-ac careers.

R1 Public University, United States Let me first thank the discussants for their thoughtful comments and Paula for organizing this online panel. Most of the discussants are junior scholars writing about how they and other scholars in similar positions might make themselves more marketable on the job market or find alternate career paths. From that perspective, they are absolutely correct in their advice. They are doing everything they should to survive in a tough job market. Where I have concerns is the implications their advice has for the field as a whole, particularly the moves towards interdisciplinarity and transregionalism. While marketing oneself as able to teach across several disciplines and “Asia” as a whole—including not only all of East Asia but Southeast Asia and even South Asia in some cases—is undoubtedly the correct tactic for those competing for an ever-dwindling set of jobs, I am worried that we will begin to internalize this not merely as a convenient tactic but an actual good. Let me suggest, perhaps controversially, that there is no good reason to teach China, Japan, or Korea together, much less other “Asian” nations. Sure, they are relatively close geographically, and they have had some cultural intercourse and influence on each other, but the same could be said of any number of European nations. Yet no dean would ever consider proposing that French, German, and Russian literature should be covered by a single faculty hire. There maybe narrow contexts where teaching these areas together makes sense (transnational Confucianism, perhaps, or European naturalism), but these are areas with distinct and mutually unintelligible languages, social customs, cultures, and canons. This is recognized in the case of France, Germany, and Russia, but not, it seems of China, Japan, and Korea. One suspects that Takeshi Watanabe has the right of it, that “‘transnational’ in job ads can be a disguised shorthand for wanting one body to cover as many multiple areas as possible.” “Transnational” and “interdisciplinary” sound good (even transgressive) at first blush, but are really just an excuse to save money by having one person cover several areas despite their having, really, very little in common. We are faced with an “Asian fusion restaurant” syndrome, where several distinct cuisines which are not really similar or even palatable together are thrown together because they are exotic to Westerners in vaguely similar ways and, really, who has time to figure out all those different countries? We just want one place where we can go and get a mishmash of dishes that are both interestingly foreign and adapted to our taste, and please take your ideas about cultural specificity and go back across the Pacific where people care about that sort of thing. My concern is twofold. First, we run the risk of seriously underserving our students when we market ourselves as “Asianists.” My training is in modern Japanese literature. I could probably read up on modern Vietnamese literature enough to superficially teach a short story or two as part of an “Asian literature” course, but my instruction would seriously lack the depth and texture I could bring to a discussion of a modern Japanese short story where I have been trained in a whole historiography and literary tradition (including that tradition’s rebels and iconoclasts). We may comfort ourselves that students are at least getting some exposure to these areas even if it is superficial, rather than none, which is the alternative. But as Edward Said persuasively argued, reductive representation might be worse than none at all. As we reach into areas we have only shallow understandings of, we risk falling back on facile essentialisms forty years after Orientalism. The second concern is that if we accept these new transnational practices as a justified good (rather than a tactical necessity) and begin training graduate students accordingly, we will do them and ourselves a disservice by failing to train them in the rich depth of our disciplines. If we stop producing experts in Japanese literature who can interact with literary texts subtly in the original language and situate them in the complexity of Japanese literary and critical discourse and instead produce (for example) students who study “trans-Asian” or “transnational Asian” literature, those students will not be able to seriously engage with our Japanese colleagues or scholarship in Japan. And then what will we offer that comparative literature programs do not already offer? We will have sabotaged both our students and our discipline. Again, none of this is to take the discussants to task for pursuing careers in transnational, transregional, or interdisciplinary studies. The reality on the ground is that such tactics are necessary to secure jobs in the modern neoliberal university governed by administrators who are eager to cut costs and have little understanding of or care for the vast gulfs between regional disciplines. We should all, in fact, heed and adopt these tactics, as appropriate to our careers. My concern is that we should not jump on a fashionable “transnational” bandwagon, internalize the homogenization of Asian studies as a justified good, and abandon the rich national literatures and histories we are trained in.

Monash University, Melbourne, AU Firstly, I am struck by Mark Pendleton's comments that Japanese Studies must be both intellectually and industrially reborn. As I write this I am living in a precarious world. Before the pandemic, in early March 2020, I had been unemployed for four months like many casuals in Australia due to the summer period and I had only just accepted new contracts for the new teaching period. In two years since I graduated with a PhD at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, I have applied like many in the same situation, for job after job, postdoctoral positions, contract positions and other, in Australia, in East Asia, the United States, Europe and Japan. Only three or four weeks ago, however, I accepted an upcoming position as Japanese Lecturer at a small regional university in Australia and having examined at length Paula Curtis' excellent presentation of data for the academic year, I am truly grateful to be given this opportunity. Launching into a career and preparing for an interstate move in the middle of a pandemic, I strongly support Pendleton's call for solidarity in the neoliberalised university and I support our identification and supporting of the margins of academia. In research, similarly I am similarly interested in the movement away from the nation-state and across and in-between. My own research begins at the margins, in considering the Japanese Christian experience of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. I appreciated Ioannis Gaitanidis' contribution in discussing 'internationalization' through the Japanese lens. Teaching about the world using 'Japan' as case study resonates with me and my own research, in the intersections of culture, and in locations of cultural hybridity. The in-between should prompt us to move out of our own 'safe places'. My experience as a contract associate in universities over the past two years has itself included teaching in courses outside my own training and specialisation just as Laura Miller discusses. Rather than being to my detriment, this experience assisted me greatly, especially in the past year, as I was called upon to coordinate a modern Chinese History course and as a result of that experience go on to teach in modern Chinese History, assisting Chinese specialists the subsequent semester. A demand for Chinese history is today driven by undergraduate students interest in the area in Australia and as a Japanese Studies PhD graduate, the opportunity to work in this area allowed me to be able to broaden my understanding of the East Asian region more generally and to begin to understand better the interplay of China and Japan in history, especially in the twentieth century. Finally, I read with great interest Takeshi Watanabe's comments about the COVID-19 world. In Australia too, the impact on university positions is largely yet to be understood and in a neoliberal state where government support has dwindled to around 30% of university budgets many institutions appear badly exposed. Yet, more than ever, in the midst of this global crisis, the humanities are needed to make sense of a post-COVID reality. In Australia, there is already talk of a Tasman-bubble allowing movement incorporating New Zealand and Australia and this may also extend to Pacific Islands. As Watanabe writes, only time will tell as to what shape the rebirth of Japanese studies in a post-COVID world will take.

Doshisha University, Japan To Mark Pendleton. Thank you for a terrific article. You describe the closing of the Centre for East Asian Studies at Durham as ‘a spectacular own goal’. That is probably the politest way of putting it. Sadly it was only one of a number of centres that were closed around that time. The list also includes the Contemporary Japan Centre at Essex University (where I did an MA 1992-3), the Scottish Centre for Japanese Studies at Stirling, and the Japanese Studies Centre at Birmingham University. They all lacked clout in internal university politics and they were too dependent on short-term outside funding. The closing of these places may not be such a big problem if students at UK universities had access to courses or modules about Japan while studying other degree subjects, but they don’t. History (for example) usually covers the UK, Europe and the British Empire/commonwealth. So Japan is excluded (as well as Korea and many other places). You write that “Appointments have been made who explore connection across and between ‘areas’, constituting new areas of their own” and that is something to give us hope. The problem used to be that if a university library didn’t have a collection of books on (say) Japanese politics, then the university could not offer that kind of course without making a massive investment in new books. With everything going online that may be less of a problem going forward. So one possible way forward for Japanese studies in the UK would be to support scholars and teachers who are not necessarily specialists only in Japan. Reading Melinda Landeck’s comments about faculty in small Liberal Arts colleges teaching interdisciplinary programs in the USA made me think that this is not a UK-only phenomenon.

University of Texas, Austin, United States Reading these round-table contributions, I was struck by how they implicitly problematize an older incarnation of Japanese Studies. A funeral is the wrong time to speak ill of the deceased, but many of the recommendations for our “reborn” Japanese Studies read less like desperate responses to a collapsing job market than sensible professional practice. I found myself wondering whether our dearly departed Japanese Studies was not, in fact, always something of an insecure, insular, habit-bound grouch. Why would Japan Studies specialists outside Japan speak primarily, much less exclusively, to other Japan Studies specialists? Why was this ever considered desirable much less sustainable? Why shouldn’t Japan specialists address the broader questions of comparative literature and world history? Making Japanese literature central to any consideration of world literature seems like an essential intellectual project. So does making Japan integral to world history. The daily demands at an R1 vs. a SLAC are different, but worthwhile research and teachings questions are constant. Gaitanidis challenges us to “train students to see larger ideological discourses and become aware of their own role in learning.” Hard agree. The painful question is, how did old-man Japanese Studies ever get enmeshed in East-West essentialism and clumsy universalism? Not to speak ill of the dead. In my own current passion of digital humanities, shouldn’t Japan specialists be shaping core questions? Why treat the challenges of text mining Japanese, such as the lack of whitespace delimited words, as deficits rather than essential research problems? A vast portion of human communication (both digital and archival) is encoded in messy, non-whitespace delimited, scripts systems. Shouldn’t Japanese Studies address decentering digital humanities technologies away from tidy Roman scripts? A key question going forward seems to be the relationship between Japanese Studies in Japan and Japanese Studies elsewhere. Is our goal to reproduce in the diaspora a microcosm of Japanese Studies as practiced in Japan? That vision was sustainable for about two generations, but only with steady infusions of cash from the Ford Foundation, the Japan Foundation, and then the Bubble Economy. But it now seems neither desirable nor possible. Let us reverse the question. Wouldn’t we want a Japanese specialist on the US Civil Rights movement to offer a non-US perspective? Certainly, good research needs to be grounded in primary sources, and to engage the secondary literature. But where is the greatest potential for a new insight from a Japanese scholar? A hypothetical Suzuki Michiko at Nantoka Daigaku has a full teaching load and lives in Chiba. What can she offer an American historian with an on-campus archive and a family connection to the movement? Don’t American historians still read Tocqueville precisely because of his empirically grounded outsider insights? And don’t globalization initiatives at MEXT and Nichibunken reflect a hunger for just that perspective? I do not want to minimize the real challenges facing area studies. But in my own graduate advising, I try to build the death of Areas Studies into dissertations topics. What if there are no Japan Studies jobs, but only jobs in world history or modern literature? What sort of Japanese Studies dissertations might lead to a campus visit? What topics might make for a great job talk? These questions lead to a new vision of Japan Studies focused on broad thematic questions, ranging from foodways and sexuality to more conventional questions of economic development and political thought. They afford little room for conventional national histories, but force us rethink “why should anyone outside of our specialty care about Japan?” Such dissertations will be more demanding than those of a previous generation, since they will require the same mastery of Japanese primary sources and also deep engagement with new questions and methods. But let us imagine a new cohort of Japan Studies scholars who are known for their exceptional mastery of thematic and comparative questions. A model here is the “anthropocene,” where a range of Japan Studies scholars such as Julia Thomas have made Japan central to broad, non-Japan questions. Central to the “rebirth” Japan Studies will be asking “how might my research become essential outside Japan Studies?”

United States It seems to me as though two distinct, yet related, conversations are happening when we talk about the “death and rebirth” of Japanese studies: one is disciplinary in nature (“What sorts of questions should Japanese studies address, and how?”), and the other institutional or, if you like, existential (“How can Japanese studies continue to secure financial support from universities such that it can endure as a field?”) I fear, in reading some of the responses to this very timely roundtable, that we are slipping too easily from one to the other. To get straight to my point: discussions of the most productive, ethical, and rigorous shape of Japanese studies are critically necessary, but cannot substitute for a discussion of the larger institutional contexts in which the field is placed. No matter how “liquid” our area studies, no matter how crucial to understanding the world, to an academic administrative culture with an exceedingly narrow imagination of what constitutes “utility,” it is only so much capital being spent on “extraneous” pursuits. I was therefore somewhat concerned that many of the panelists’ responses seemed to imply that if we can just find the right version of Japanese studies, if we can just turn our own thinking toward certain kinds of utility for our research and teaching, then Japanese studies will achieve its rebirth. From my perspective as a graduate student involved in advocacy efforts at my own R1 institution, it seems that if we in North American universities are not able to reform institutional governance structures and faculty/grad student bargaining power, that rebirth will be stillborn. By no means is this a crisis that is new, nor is it unique to Japanese studies. But two financial recessions in 12 years are exacerbating trends that have been ongoing since at least the 1990s. At my university, at least, the COVID-19 emergency has prompted hiring freezes and staff furloughs, while at the same time upper-level administrators continue to make over $2 million per year in salary. Dr. Landeck comments that we must think across disciplinary boundaries in designing our courses to form connections with faculty in other departments. Quite so. The crisis of Japanese studies is the crisis of the humanities, and solidarity is the key to our survival. This is why I feel that the most pressing of the disciplinary questions raised in this roundtable is that which is perhaps most succinctly stated by Dr. Pendleton: the challenge of inclusion. I was shocked at a recent annual meeting to hear senior colleagues, speaking on the issue of inclusivity within the field, say that we should refrain from “rocking the boat” in trying to build large networks of solidarity both within and outside our home institutions, that we might risk the ire of provosts and presidents itching for the excuse to cut our programs. I would instead side with Grace En-Yi Ting, cited by Dr. Pendleton, who argues that greater inclusivity within North American Japanese studies and a renewed commitment to challenging our white supremacist inheritance from our Cold War roots is a matter of disciplinary life and death. This is true not only for the field’s continued ethical viability but also, as the recent uproar around Harvard’s decision to deny tenure to Lorgia García Peña and suspend its search for an ethnic studies professor makes clear, for our efforts at winning over the students whose tuition dollars and fundraising potential seem to speak louder to university administrators than we are able to. Japanese studies’ rebirth, then, must be predicated on a reconsideration not only of the kinds of research questions we ask, but also of our own institutional status, the securing of which must involve wide-ranging alliances with faculty, students, and staff in order to most forcefully assert our necessity. There can be no rebirth without organization and advocacy, as many of the elements that make Japanese studies so vitally important are those very questions which push against the current neoliberal and managerial ordering of so many North American universities.

Independent Scholar, Grand Rapids, Michigan, United States In a live session the dialogic nature would allow me conversational style and thoughts composed extemporaneously, rather than polished prose. I will compose my comments in that way. 1) I wonder if any panelists can speak to the circumstances of Area Studies in other countries; in other words, how peculiarly culturally and historically situated is the present state of teaching and research of Japan in USA or the Anglophone world? 2) The perennial question of vocationally pragmatic courses and college majors versus concentrations of expertise that display no direct or immediate application can't be avoided. Laura Miller identifies that directly, but surely it abides in the minds of the others, too. My question is how each presenter addresses those challenges that administrators may raise periodically? It seems to be connected to monolinguals who imagine universal meaning and transparent translation is just one software breakthrough away; that context only matters for things like humor, verbal arts, emotion, religion, or politics and thus is not so important for International Studies. 3) Within anthropology in USA there has been a movement away from conference panels with Japan as the organizing principle. Instead, to diffuse Japanese research into thematic and comparative discussions, presenters have been urged to join with colleagues not affiliated with Japan as their common denominator. One consequence is a "de-ghettoization" of Japan Anthropology. Another consequence is to bring the depth of context and meaning that is rooted in Japan to panel discussions that lack that ground of shared knowledge. My question for the round-table is with regard to the Re-birth of Japan Studies: is there net gain or net loss by diffusing Japan expertise into wider scholarly circles, rather than in concentrating expertise inside a Japan-centric arena? Which approach seems most likely to produce more and better scholarly fruit?

Meiji University, Tokyo, Japan I was grateful to read Professor Gaitanidis’ comments on the teaching of “Japanese Studies” courses at Japanese universities. In particular, I love the idea of using “Japanese Studies” courses to “teach about the world, using ‘Japan’ as a case-study, and vice versa.” I am also a beneficiary of Japanese government and university initiatives to hire more foreign faculty and focus more on English-language instruction. I currently hold a permanent position at Meiji University in the Department of Political Science and Economics, where I teach “English” classes with titles like "Gender in English-Language Media” and “Robots, Cyborgs, and Virtual Worlds,” as well as a seminar on contemporary Japanese cinema and (as of this year) a course designed for international students called "Haunted Japan.” Though many of my classes are technically “English” classes and would not be classified as "Japanese Studies," some classes are focused specifically on Japanese media and popular culture, even if the educational goal may be to improve English listening, speaking, reading, and writing fluency. In practice, similar to what Professor Gaitanidis describes, I have struggled with not only how to deliver meaningful classes to students from a wide range of backgrounds and with varying levels of English fluency, but also with the deeper question of what "Japanese Studies” means, particularly when it is taught a) at a Japanese university by a professor who did not grow up in Japan, b) to mostly Japanese students, and c) in a mix of Japanese and English. Many of my students have been quite blunt about the fact that they took my class so that they can "talk to foreigners about Japan in English,” and I know that Meiji has promoted my types of classes as an opportunity for students to become "global citizens” (which, as Professor Gaitanidis describes, often means strengthening one’s Japanese identity and then promoting Japan overseas). In my three years at Meiji, there has also been a big expansion of international exchange programs, which reflects a harsh reality that many Japanese universities are dealing with: the declining birth rate means lower domestic enrollment numbers, and so Meiji is increasingly seeking revenue from international students. (Needless to say, this plan has hit a wall due to COVID-19—in my department, at least, all short-term and long-term study abroad programs have been canceled for spring, and fall programs may be canceled as well.) Under normal circumstances, though, this expansion has meant more “Japanese studies” classes created specifically to introduce Japanese culture to non-Japanese students. Occasionally, Meiji students have also had the opportunity to join these classes (again, often with the idea that they are the “experts” and can act as guides for the international students). How does one teach "Japanese Studies” in Japan to both domestic and international students without perpetuating certain essentializing / Orientalist perceptions of Japan and Asia? In my own Japan-focused classes, at least, I have tried to encourage students to think critically about their own perceptions of “Japanese-ness” and how different types of Japanese media both perpetuate and challenge these perceptions. We talk about the concept of “national cinema” and how the very idea of such is becoming outdated in a time when so much cinema production is outsourced to other countries. But at the same time, we talk about how a country’s artistic output is still very much tied to national pride and identity (using the recent controversy over Koreeda’s Shoplifters as an example, as well as Japan and Korea’s very different strategies concerning government support for the film industry). For the first time this semester I am teaching a course with both exchange students and Japanese students, and I’m eager to see how discussions about Japanese media and its relationship to national identity will play out. It's clear from Professor Gaitanidis’ comments that many professors and departments are actively working to unpack and reframe the concept of both area studies and “Japanese Studies” as they pertain to English-medium instruction in Japan. While COVID-19 has made a lot of things uncertain, I look forward to seeing how these programs and methods of instruction will continue to challenge students and faculty to re-think "Japanese Studies” as a concept.

La Trobe University/ Lecturer in Japanese (part time, continuing), Australia In many ways I write this as I always do nowadays - with 5 tabs open, an unfinished ppt lecture minimised, and with 3 word docs and 2 forgotten email windows cluttering up the bottom of my screen. I write in haste after seeing Paula's "4 hours left" call to submit to the roundtable late on an Australian evening - a sports cooking show on the telly, a cat by my side and a dying fire in the grate. My thoughts are scattered - is Japanese studies dying? Is it about to reborn? Is there an Evangelion pun that I can slip in here? You can (not) redo; You can (not) advance; You can (not) ... At the end of last year and for the first few months of this - before Covid-19, before work from home, before casuals positions in Australia where jettisoned across universities, before I taught an online grammar tutorial which finished with three out of forty students (their screens set to black on z00m and their audio politely muted), I was fighting with La Trobe to preserve the level of Japanese being taught. In the days before Christmas a restructuring of the language syllabus at my university was slipped into being which saw, in a nut shell, all languages expected to be taught with the same entry points and the same fluency goals based on the Common EU Framework. The goal, we were told, was student retention (Japanese consistently has the highest level of retention post semester 1 - after the less serious students are frightened away by the hours of grammar and vocab learning). The model that my colleagues and I in Japanese were asked to adopt would have seen us teaching Genki 1 over a two year period - a text that I taught in two semesters as an ECR in New Zealand - placing us at least a year behind the four+ other institutions teaching Japanese at a tertiary level in Melbourne. Students from 2021 onwards would effectively be charged for two years at undergrad and two years at postgrad to attain the same level of language study that their peers at other institutions are offered at undergrad level. (I'm pleased to say that our head of programme managed to claw us into a position that will see us only a semester behind). I have no idea how widespread this attitude is in Australia, but I know it was one that colleagues at my former institution in New Zealand are fighting on two fronts - with Mandarin, and with European languages. I worry about our 2021 courses - but I'm excited as well. Currently we only have one content/culture unit at each level which is 100% Japan focused (in addition to language I teach an East Asian Pop culture course which meanders through China, Japan, India and Indonesia - with pit stops at Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, the Philippines, the Ryukyus). An extra semester means that I can shoehorn in more cultural content and literature alongside introductory grammar. A potential phoenix egg in the ashes of the old programme. The other thought that is tap dancing through my brain lies in popular culture. I am trained in Japanese literature and for most of my career have worked on masochism and violence in literature written by women, but more and more I find myself writing on cosplay in an emerging field filled with scholars who have little to no Japanese literacy or interest. Does it matter when cosplay is something that is global? That Japanese blame on the US? Does it matter when humans have always dressed up as our heroes and our worst fears? I think it does. And I think this lack of awareness harks to a general lack of awareness or appreciation for those that have gone before. Just before I saw Paula’s tweet, I saw another form a journalist who had just 'discovered' that fan studies was a thing and wanted baby academics to send them ALLLL of their theses. I had a quite chuckle to see fan studies scholars ask if the journo wanted all of the last 30 years. Do I have a solution or a suggestion or a way forward? No. All I have is a lecture to try to finish before tomorrow and a pocketful full of Evangelion soundtracks. You can (not) fly me to the moon.

JET Program, Niigata City, Japan I do tend to agree from my background as a student that pop culture is not overly emphasized. Do students clamor for it too strongly? Yes, in my opinion. But that is probably only 1/3rd of even American students. And perspectives from China may overlap and diverge in many ways. I think many faculty continue to understand how to approach this perspective. Even an Anime Survey class (as some universities teach) can be a very interesting jump off point to talk about many things. I have certainly heard some overlap between cultural and social theory and certain types of media being explored here. The career side was handled very well by Dr. Pendleton, from my view outside the window. There are serious career considerations to take today. For some of us, we will see that as a responsibility to take our work outside of academia. Tis a Neoliberal solution, but seeking out major donors might be an avenue for greater research and teaching freedom. Sadly, we do now live in a Neoliberal World.

University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States The ability to teach beyond one's narrow research specializations is necessary in thinking of how Japanese Studies may be reborn. As almost all of the panelists have indicated in their comments, one cannot expect to teach courses on their regional, disciplinary, or temporal specialization. However, I would like to ask the panelists how they see language pedagogy fitting into the post-Cold War (and perhaps post-COVID-19) Japan Studies 2.0. Many jobs, especially at liberal arts colleges and R2 Universities, seek Japan generalists who have experience teaching language. How can graduate programs in Literature prepare graduates to be competent language teachers? Another trend in the field, especially at smaller and regional colleges, is to have language specialists teach culture courses. I do not desire to denigrate the overlooked work of language lecturers - but I have seen many Japanese popular culture courses that do not engage in critical assessment of language, national identity, or the affordances of certain media formats. Often these courses are billed as "Japanese Culture through XXX." How can graduate programs in language pedagogy or linguistics train graduate students to engage in the type of critical Japanese studies, such as at Chiba University, that they can then implement in their culture courses?

Princeton University, United States I have a question for the panelists that I've been wondering about since I started training graduate students. Scholarship in premodern Japanese studies requires rigorous philological training gained through seminars focused on close readings of texts written in classical Japanese and kanbun. At the same time, there is an increasing need to prepare students for so-called alt-ac careers and even within the academy for less-specialized teaching and other skills. Since I officially teach one graduate seminar a year, it seems incredibly difficult to succeed in both of these endeavors, at least through formal coursework. What's the role of philological and text reading seminars in the 21st-century university? How can they be best taught?

Dartford Grammar School for Boys, Kent, UK Dartford Grammar School for Boys has over 500 students learning Japanese. Half of all year groups from Year 7 to 11 study Japanese and take their Japanese GCSE in Year 11. We have approximately 80 students in Year 12 and 13 studying on the International Baccalaureate Ab initio and language B courses. Additionally we run the Japanese Excellence Programme for Years 7 to 10, which is an intensive learning course where 35 students per year group have an additional 90 minute lesson a week to study kanji and culture in greater depth. Our Year 10 JEP students will take the native speaker KanjiKentei examination as we have now been accredited as a host school for this examination. We gained Sakura Network status in 2016 and have outreach commitments to two primary schools in the local area, and have worked across a range of other schools to support Japanese studies and provide outreach teaching. We provide opportunities for our own students to experience Japanese outside the classroom through exchange programmes with our partner schools in Japan, residential trips at Chaucer College Canterbury, and day trips to the Japanese Department at Oxford University. We welcome visits from universities and research institutes who are interested in Japanese teaching in the UK and have also received visits from Waseda high school as part of a research project on immigration. We would really like to provide our older students with the opportunity to work in apprenticeships at Japanese companies, or gain work experience there while they are still at school. However, we have found resistance from companies who prefer to work with university graduates. Despite the fact that we have such a large number of students studying Japanese, we tend to have low numbers continuing to higher education. Therefore, we would welcome institutions coming to Dartford Grammar to promote courses and give Japanese workshops. We would also love a partnership with a sponsor who could support the Japanese Excellence Programme, which we run in parallel with the Department for Education's Mandarin Excellence programme, but receive no funding for. We are very interested in working with a variety of institutions to support the future of Japanese Studies, whether it be us supporting others to raise awareness of Japanese, or others supporting us to give our students the best opportunities.