A Guide to Twitter and Social Media Safety for Academics (and Everyone Else)

Paula R. Curtis

May 20, 2022

At the start of 2021, I created A Guide to Best Twitter Practices for Academics (and Everyone Else), which recommended ways to effectively and respectfully use Twitter. As I have written elsewhere (and is generally apparent to anyone who engages online), not every person using social media is doing so with good intentions. This article is an extension of the Academics Online series of virtual events on digital harassment in Asian Studies hosted through the Association for Asian Studies’ Digital Dialogues. Although public-facing work and digital engagement are increasingly demanded of educators, students, and various types of workers, they are not a standard part of professional development skills or curricula, nor is how to navigate these online spaces and to protect oneself in the process. This article therefore offers practical safety tips for managing one’s Twitter experience, whether you’re learning how to recognize questionable users, in need of help mass blocking trolls, or thinking more broadly about security.

You can navigate to any subsection of the article via the links below. If you want to return to these quicklinks, you can use the “Top ▲” button on the bottom right of the page to jump back to beginning at any time:

Why Do We Need to Know This? Don’t Harassers Get Bored?

Why Twitter?

Spotting Suspicious Accounts

Common Antagonistic Tactics

Do We (Not) Respond?

Gradations of Disengagement

Doxxing

Putting Yourself First

Not All of Social Media is a Dumpster Fire

Why Do We Need to Know This? Don't Harassers Get Bored?

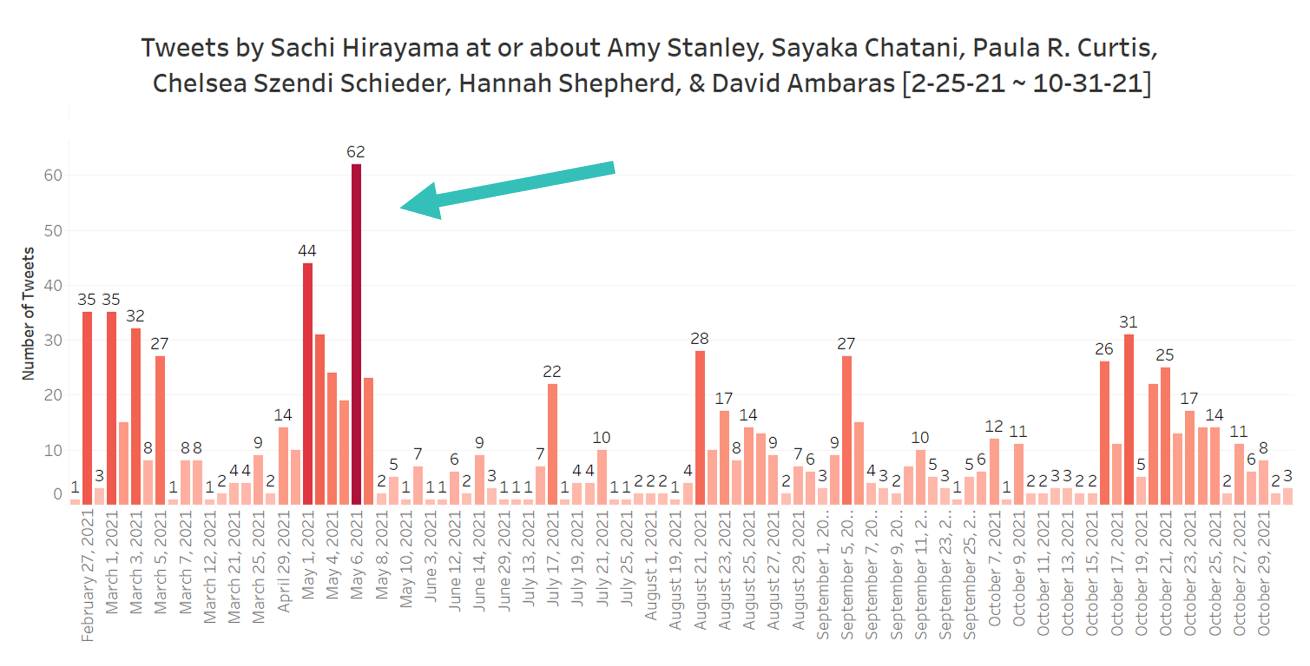

If you attended our previous Academics Online sessions, particularly Session 1, then you may already have a good sense of the danger that extremist activism can pose, even if you do not personally use social media. Session 1 (for which videos are available) featured scholars of China, India, Japan, and Hong Kong discussing the use of digital spaces for targeted harassment of scholars, journalists, and others who publicly speak on hotly debated issues. Right wing populism, historical denialism, and conspiracy theories can be fueled by online communities that seek to radicalize and grow their followers. Scholars have faced ongoing harassment, including misrepresentations of them and their work in the public sphere. They have had employers or funders contacted, and even faced threats of rape or death. Though it is simple for those who do not engage online to suggest that the attacks some people face are simply one-offs by users who will get bored and move on, all it takes is a single person with an agenda and/or their network to draw out that harassment over an extended period of time. In my recent article in Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus,1 I highlighted one such example of instigation and amplification. The image above shows data I collected on a single harasser with a very large following on Twitter. This person spent over 8 months tweeting at or about me and the five scholars who fact-checked a controversial and ethically dubious article on comfort women in WWII, a topic that always draws out trolls on social media. As seen in dark red and indicated with an arrow, in a single day, this user tweeted as many as 62 times about us. And in this case, these 62 tweets were solely about one of the writers. Imagine your phone buzzing with threats and negative statements about you 5 times an hour for twelve hours straight. That’s 60 times in daylight hours. Once every 12 minutes. And those are just messages directly about you: messages that use your face, refer to you by name, or reply to one of your threads or posts. I could have included more detailed data on replies or indirect references, but the bare minimum was illustrative enough on its own. Whether or not you turn off those notifications, the content is still there, as is the knowledge that it’s happening, and the knowledge that others are seeing it. As much as we would like to believe that these things pass, sometimes they don’t. Sometimes there are strategic and organized attacks being used by a specific community to discredit and intimidate our friends and colleagues. These are challenges that we must be aware of and prepared for.Why Focus on Twitter?

There certainly are other social media platforms academic organizations, departments, and individuals use to communicate, namely Facebook and Instagram.2 These platforms can be equally useful for sharing information to broader communities on or off campus. That said, Facebook and Instagram are not really designed for rapid sharing and discoverability in quite the same way as Twitter. Most people who still use Facebook and Instagram, particularly younger individuals, tend to keep their profiles private or only add known friends and family to avoid scams and fake accounts. Compared to more interactive platforms (like Twitter or TikTok) users who want to share or locate content, especially for academic purposes, don't search as often through hashtags or seek out public groups on Facebook or Instagram, which can make these venues a bit more closed-circuit. In contrast, Twitter more seamlessly integrates sharing features, communities centered on public hashtags, and content searches. There is no need to necessarily "join" a community, as on Facebook, and given that image sharing is not the main focus, as on Instagram, user profiles tend to be public more often. The ability to stumble across or search for users or topics more rapidly, as well as share posts more broadly, has made Twitter an effective platform for high speed communication, though this discoverability also invites harassment just as quickly. As such, the remainder of this article will focus on privacy and safety issues for Twitter.Spotting Suspicious Accounts

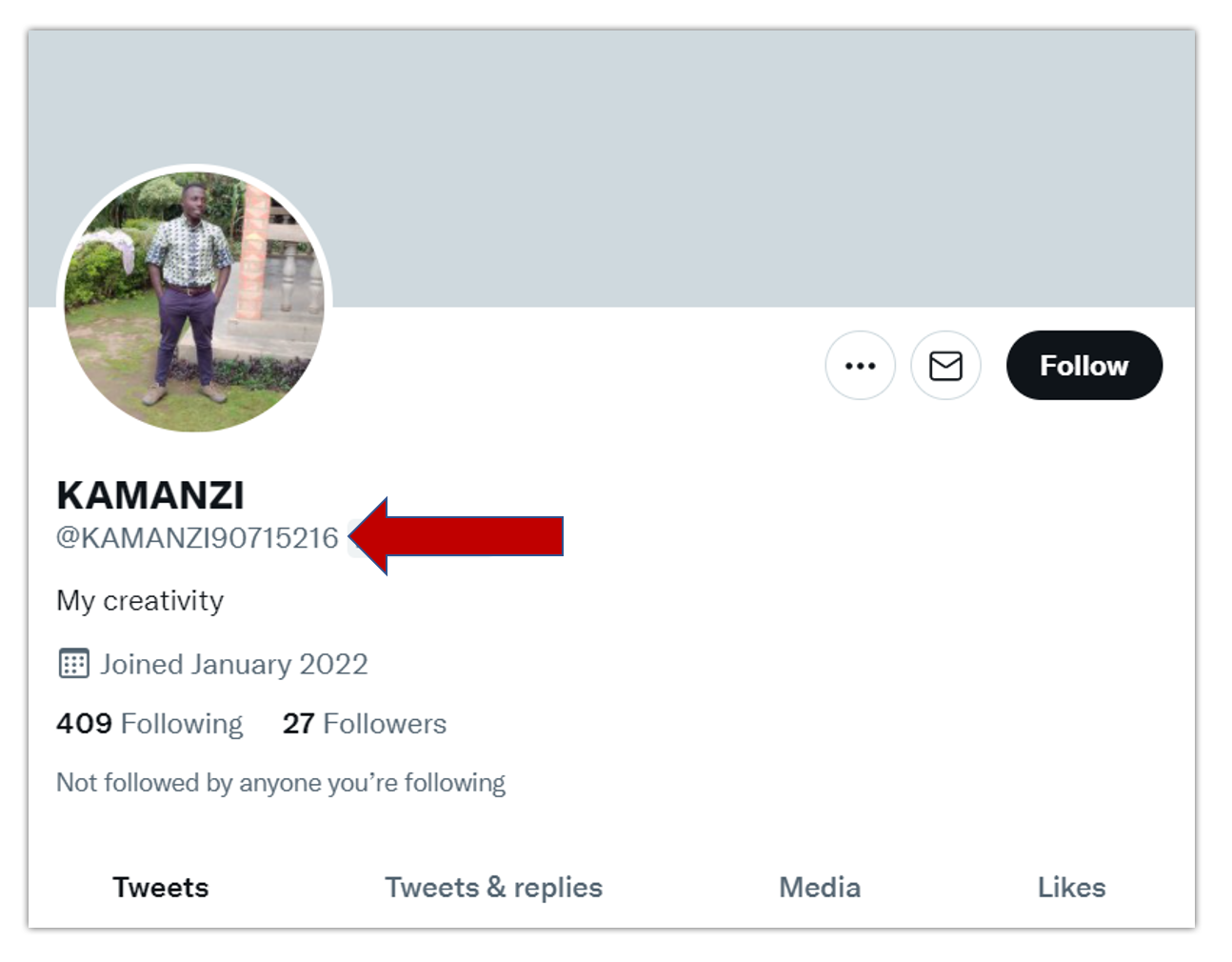

Where can our awareness of bad actors in the Twitterverse begin? Given the very public nature of Twitter and the ease with which content can be shared, encountering suspicious accounts is inevitable. When we get a reply or a follow from such a user, we often ask ourselves: Who IS this person? Are they an automated bot? If they have the blank, default Twitter user picture, are they actually a real person who has only just created their profile, or could they be a fake account? Are they just someone I suspect I just don’t want to have follow me? The most important thing to remember from the beginning is that whatever the reason might be that you don’t want a person interacting with you, your choice to not engage with them is valid. There is no rule that anyone who follows you is entitled to follow you. This is a decision in your hands. So what makes someone’s Twitter profile suspicious? What are some common characteristics that may be red flags? Below I categorize some standard questionable patterns.» String of Random Numbers Person

» Questionable Follower Ratio Person

» Just Joined/New Profile Pic Person

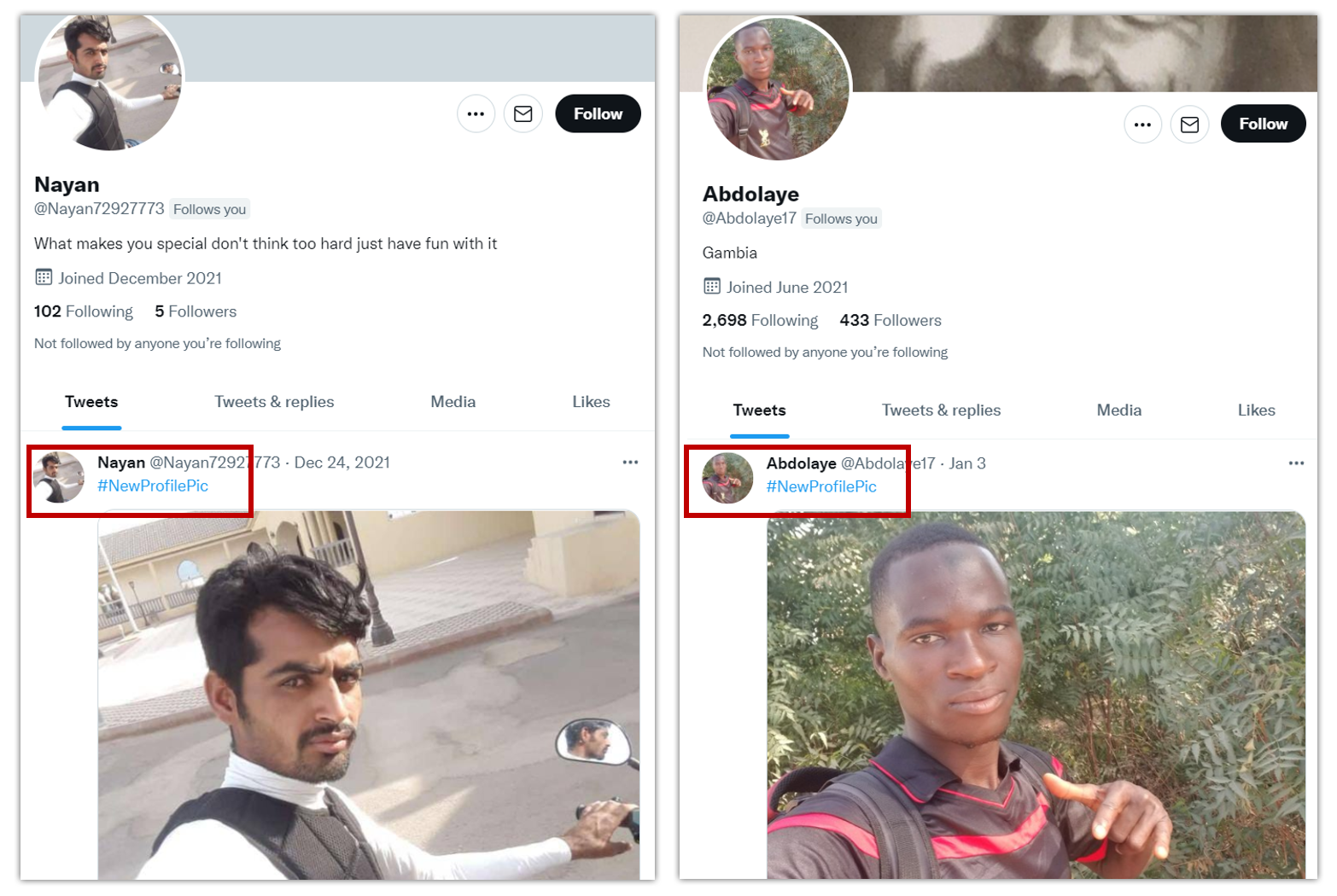

Similar to the questionable follower ratio indicating suspicious or bot accounts, the Just Joined/New Profile Pic Person is very common as well. The account that follows you may will have been created that month or in the last couple of months. The screencaps I took below were taken in December 2021 and June 2021 respectively, so when they followed me they were brand new fake accounts. These recently created accounts will sometimes have only one post, and may be something about just now joining the platform. Using the hashtag #NewProfilePic is one seen often enough to be a dead giveaway for a bot account.

Looking at these two profiles above, you’ll note that the one on the left adheres to our "string of random numbers" pattern for the username, while the one on the right does not. However, they both have almost identical photo poses and the only tweet they’ve made since being created is #NewProfilePic. I have also seen instances in which the first picture posted to the account was something stock (like a bunch of flowers or a beach) with the #NewProfilePic tag. Some of the accounts may also have "#NewProfilePic" in another language, or have #NewProfilePic as their first post and then a bunch of retweets afterwards. It's not clear to me what these (or any other) bots accomplish, but after 20 of them have tried to follow you you begin to see these patterns. It is also worth noting that many of these fake accounts disproportionately use images of people of color.

» The Humble Gentleman (Who Loves Life)

The Humble Gentleman (Who Loves Life) also appears in combination with many of these other characteristics. In my experience these bot accounts are frequently pretending to be men. The user bio makes claims that the person is humble, honest, happy, fun-loving, has a great personality, or sometimes is into God (or his country). There are a lot of variations, but such accounts are rarely very active. They could include a bunch of random photos that seem to have been scraped from stock scenes of pretty landscapes or to have been stolen from someone’s personal account or online profile. On occasion these Humble Gentlemen feature a series of selfies to make it seem that the account is a real person (see an example of this in the "Person Only Following Women" archetype below).» The Military Person (Who Loves God or Wants a Relationship)

The Military Person is very similar to the Humble Gentleman, though may not always be a man. These accounts can have normal photographs of a person or be an official-looking picture of a person in military uniform. Still, on occasion, the image won't seem to have any connection to the military at all. Their bios might identify them as "US Navy, Loves Our Country" or include some kind of phrase about how they are "looking for love" or "looking for a serious relationship." In some cases, the images or names of military persons have been lifted directly from Wikipedia or another website and used to create the bots. Here is one example where searching a public figure's name revealed over a dozen fake accounts:

» The Trustworthy Doctor

In addition to military personnel, we also find that fake accounts regularly claim to be doctors or surgeons. I'm not sure exactly why, but my guess would be that they are trying to play to common perceptions that military figures and doctors are trustworthy people. The two examples below effectively illustrate a combination of our above mentioned characteristics in both English (left) and in Japanese (right).

» The Person Only Following Women (or Another Group)

Similar to how many bots will only follow politicians, news outlets, or other notable peoples or organizations, I've also found that many fake accounts have been programmed to strategically follow women and/or a particular field of interest. To the left you can see a standard Humble Gentleman Account that began following me in December 2021 (a recently created account at the time). The bio insists "God is the only way to success" and the feed is full of seemingly random professional photos of the person whose image is used. Some kind of strange site that I dare not click on is listed in the profile as well. Although there is not a questionable follower ratio, when we examine the accounts the user is following, we find that it is almost exclusively women in Asian Studies and/or employed in Asia-related media. This suggests to me the bot targets a specific kind of account, which can be a warning sign when paired with the other dubious profile characteristics.» The Person Who Only Retweets, Tweets Excessively, or Only Tweets Stock Photos

» The Celebrity or Famous Person

Every now and then I get followed by Keanu Reeves. Sadly, not the real Keanu Reeves, but a bot or fake account using his photo. Much like our military people whose info and images have been scraped from the web, you may find that some accounts use the likenesses of famous celebrities or other public figures (even if they may not be recognizable as famous to you). Below I provide an example of an account pretending to be a notable person that also incorporates many of our red flags. At a glance, Warren Steve does not have random numbers at the end of his handle, so that might seem promising. Looking at the bio, which is in Japanese, he notes liking food, people, Japanese temples, and that he generally admires all that is Japan. He could just be a guy into Japanese culture. His join date, December 2021, is a month before he began following me, which gives me pause. His following/follower ratio, 612 to 52, is also a red flag. If we glance at his media-based posts, seen in the top right of the gif, his feed consists mostly of stock photos of nature and Japan (Tweets Only Stock Photos account!). The stock photos also seem a little at odds with his serious businessman demeanor. So how can we search to find out who this guy is?

How Can I Show I'm Not a Bot or a Troll?

Now that you know what many of these suspicious accounts look like, it's possible to avoid being mistaken for one. Though not every fake profile will use these patterns, a great deal of them do. The most important steps you can take to identify yourself as a real person are: 1) Change your username/handle as soon as you sign up. 2) Use your real name or something close to it that would make you identifiable to friends and colleagues. 3) Fill out your user bio with some kind of identifying information about yourself, your research, or whatever else you feel comfortable and safe sharing. 4) If you think you might be mistaken for a bot or a troll, be specific about the purpose of the account. If you plan on being a lurker account that only retweets, perhaps just say that in the bio! Maybe even identify what people will find in your feed. These first steps will help people to recognize you as a real person BEFORE you begin to follow their accounts and reduce the likelihood of being mistakenly blocked. Of course, these are only surface-level characteristics of an account. In the next section I will address different types of negative activity by many accounts that are actually real people and how to recognize antagonistic behavior by bad faith actors on social media.Common Antagonistic Tactics

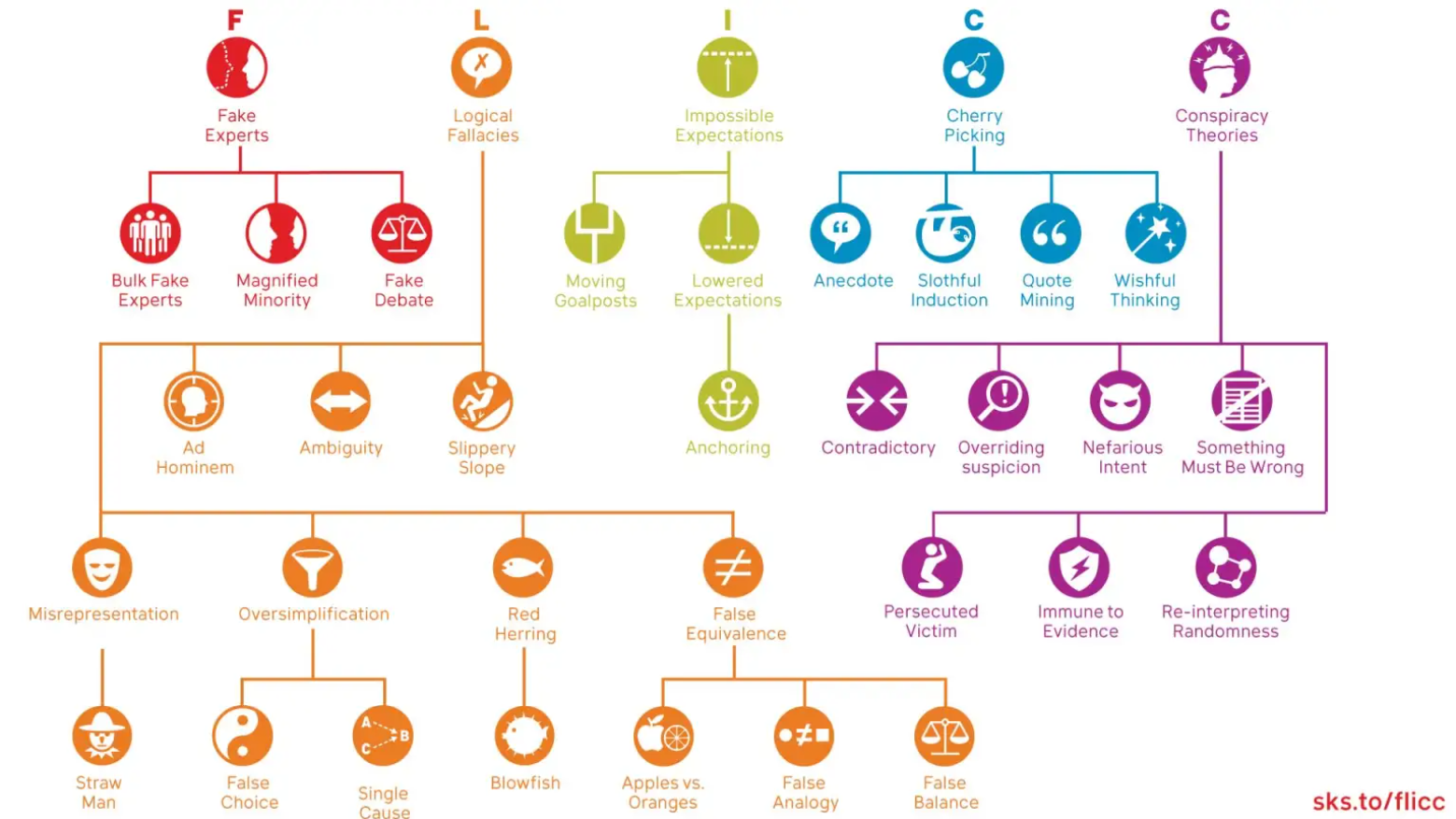

Imagine you have said something or shared something that gets you on the radar of social media trolls. A person or (potentially large) community has decided they are going to begin interacting with your posts or share your content with ill-intentions. When this happens it’s useful to understand some of the common tactics that we see from antagonizers and to be able to recognize them as statements or actions in bad faith. In an ideal world, people everywhere are logical, rational individuals. However, online, particularly in places where it’s easy to not read carefully and quickly hit the send button, unfounded hostility can come at you fast. The rhetoric and strategies used by extremist online communities are common across regions and topics. One of the most useful guides I've found to these trends in misinformation and disinformation is climate change researcher John Cook's FLICC taxonomy of science denial. His detailed infographic below lays out the core categories of Fake Experts, Logical Fallacies, Impossible Expectations, Cherry Picking, and Conspiracy Theories, as well as their many subcategories. Cook's site has some fantastic explainers and examples of each of these many strategies, and I draw on his definitions for my list below. Here I'll briefly focus on the main five in the context of Twitter harassment I have experienced from Japanese ultranationalists on the comfort women issue. In this context, trolls often focus on historical denialism of wartime atrocities, attempting to sow doubt on the testimony of, and evidence pertaining to, survivors of wartime sexual violence.- Fake Experts: Presenting an unqualified person or work as a credible source. More often than not, ultranationalist trolls who follow comfort women hashtags and news will share what they consider to be "authoritative" sources, which are often dubious right wing blogs of unclear authorship or historical materials that have been selectively excerpted to "prove" their claims or disprove other forms of evidence.

- Logical Fallacies: Presenting a conclusion that does not logically follow the argument or topic at hand. When their views are challenged, the trolls will typically jump to a logical extreme, such as, "If you are claiming the Japanese military committed a war crime in WWII, then you must be anti-Japanese and racist." In a historical context, this might be "If women enslaved for sexual purposes made money, then it was not coercive or enslavement."

- Impossible Expectations: Demanding unrealistic standards of certainty to prove or disprove a point. This is another common fallacy used to assert that inconvenient truths cannot be valid if a certain threshold is not met. For example, claiming that oral testimonies are entirely unreliable, or that we would need "credible" government records (though what those might be is unclear) if one were to ever prove that the Japanese military committed any wrongdoing.

- Cherry Picking: Selecting or acknowledging only data that supports your evidence while ignoring others. This technique of making exclusionary claims is quite common among historical denialists of comfort women history. One document often tweeted as "proof" that comfort women were not coerced, abused, or reported through dubious methods is POW Interrogation Report No. 49 (1944), which states that comfort women were "nothing more than a prostitute or camp follower." However, in the very next paragraph the report also states that the nature of the work women were recruited for was "not specified" and explictly undertaken "on the basis of... false representations"—a pretext that invalidates arguments that these women were participating voluntarily with full knowledge of the circumstances when or if they were not directly coerced. This section of the report is often omitted or ignored when ultranationalists share the Report 49 image.

- Conspiracy Theories: Suggesting there is some kind of secret plan or nefarious scheme that is hiding the truth of a matter. Among many other extreme claims about government coverups and propaganda, I and many of my colleagues faced a variety of conspiratorial claims for disagreeing with right wing ultranationalists on social media. In addition to being labeled pro-CCP spies or communists we were accused of being funded by China, North Korea, or South Korea to promote anti-Japanese positions and scholarship.

Do We (Not) Respond?

Folks who have been plagued with a wide variety of nonsense, hostility, and maybe even threats on Twitter always want to know: Should you respond? Why might one choose to reply (or not)? Should you just remove the offender and move on? It’s important to remember that an online troll is rarely actually trying to engage in a meaningful way with the person they are harassing. Which is not to say that it never happens, but by and large, these users have entered into a dispute or engagement with a specific objective such as:- Disinformation/Misinformation

- Posturing

- Entertainment

- Bad Faith Arguments & Denials

- Fodder for more Harassment or Validation

Commenting Indirectly

It may be that you’d like to call out someone for bad behavior or a questionable opinions in the public sphere for things they’ve tweeted, but then you’re faced with an ethical question—am I in fact doing more damage by directing internet traffic to their account? In addition, if you quote-tweet someone and your account is not set to private, they will immediately receive a notification and see what you’ve said, which could stir up conflict. There are two main passive ways in which people take caution not to put a target on themselves when they comment on something, even if these methods are not perfect.

» Screencapping to Comment

One method people use is taking a screencap of someone’s tweet rather than linking to their content directly. This has three relevant effects: 1) it prevents a notification being produced that you've commented on something 2) it can serve as a record of a tweet in the event that someone deletes it 3) it lessens the likelihood that someone with a significant number of followers or the ability to instigate significant harassment will see what you've posted right away In the example below we can see that directly quoting someone at many different intersections of hot button issues would likely bring out a whole host of trolls, so the tweeter chose not to direct quote them.

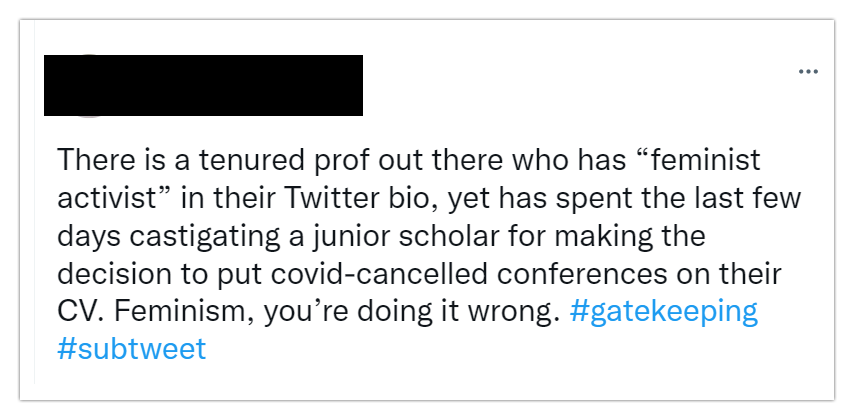

» Subtweeting

Another option to more passively comment on something is “subtweeting." Subtweeting is referring to someone in your tweet or comment while not using any directly identifying information about them. Sometimes people don’t outright say “I am subtweeting” when they write, but other times they do. This might be by using a hashtag (as seen below) or a clear statement of “Yes, this IS a subtweet.” At this point people may become curious if they don’t know who you’re talking about and go seek out whatever drama is afoot on Twitter.

Gradations of Disengagement

Let’s say you have attracted unwanted attention from an individual or even a very large group of twitter harassers. Or, alternatively, you expect to in the near future; maybe you have a publication coming out soon, were interviewed on television, or are showing a screening of something controversial that will inevitably attract trouble. When your work is public-facing there are many reasons you might become more visible on social media. Depending on how cautious you want to be and how comfortable you are engaging with questionable characters, there are various steps you can take to protect yourself or remove yourself from harm's way that range from mild to extreme, depending on what you want or need. These actions may entail controlling what you see on social media or limiting what others see of your social media. They are, in order of severity, as follows: Control What You See- muting

- restrict replies & retweets

- soft block

- hard block

- mass block

- private account

» Muting

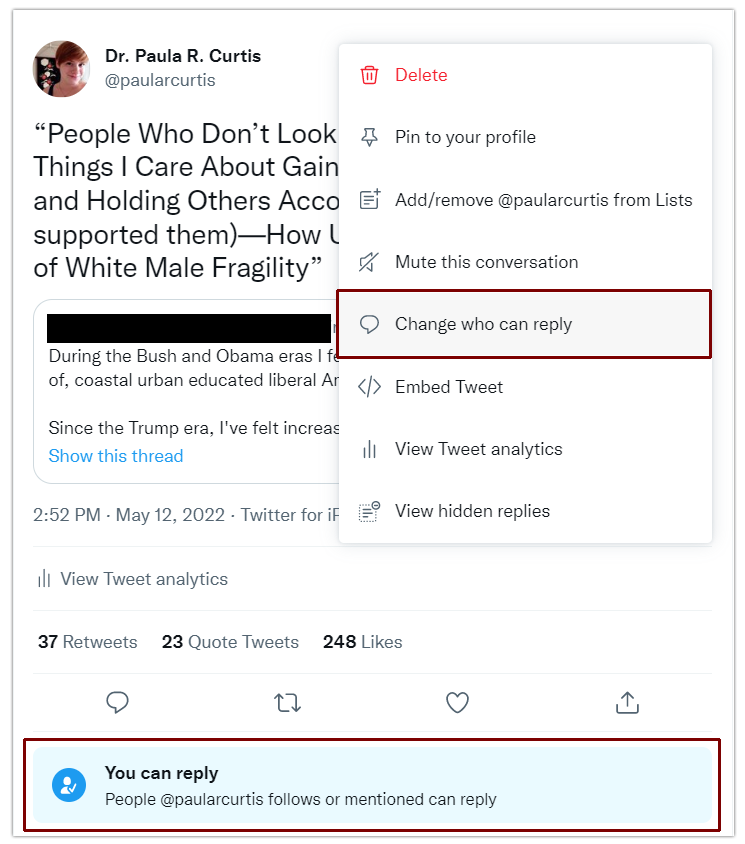

» Restrict Replies & Retweets

» Soft Block

The next level of disengagement is a soft block. A soft block is when you remove someone from following you. On your browser, you can soft block by going to the same user profile options under the three dots icon and selecting “Remove follower” (see in the gif to the left). As of writing this article, the remove follower option does not appear on the phone app, but you can soft block someone the same way by blocking the user and then immediately unblocking them. This will remove them from following your account. Soft blocking is another gentle way to show someone the exit if you don’t want them directly interacting with your content. They will not receive a notification that they are no longer your follower. If they’re a bot, no harm done. If they’re a real person, they might not notice for a while that they are no longer following you, as your posts will no longer show up directly in their feed. That said, if Twitter's algorithm shows your tweets to them because someone else liked it, they may notice they are not longer seeing your content in the capacity of a follower. If they do notice, they can always follow you again, at which point you can choose to remove them again or block them entirely.» Hard Block

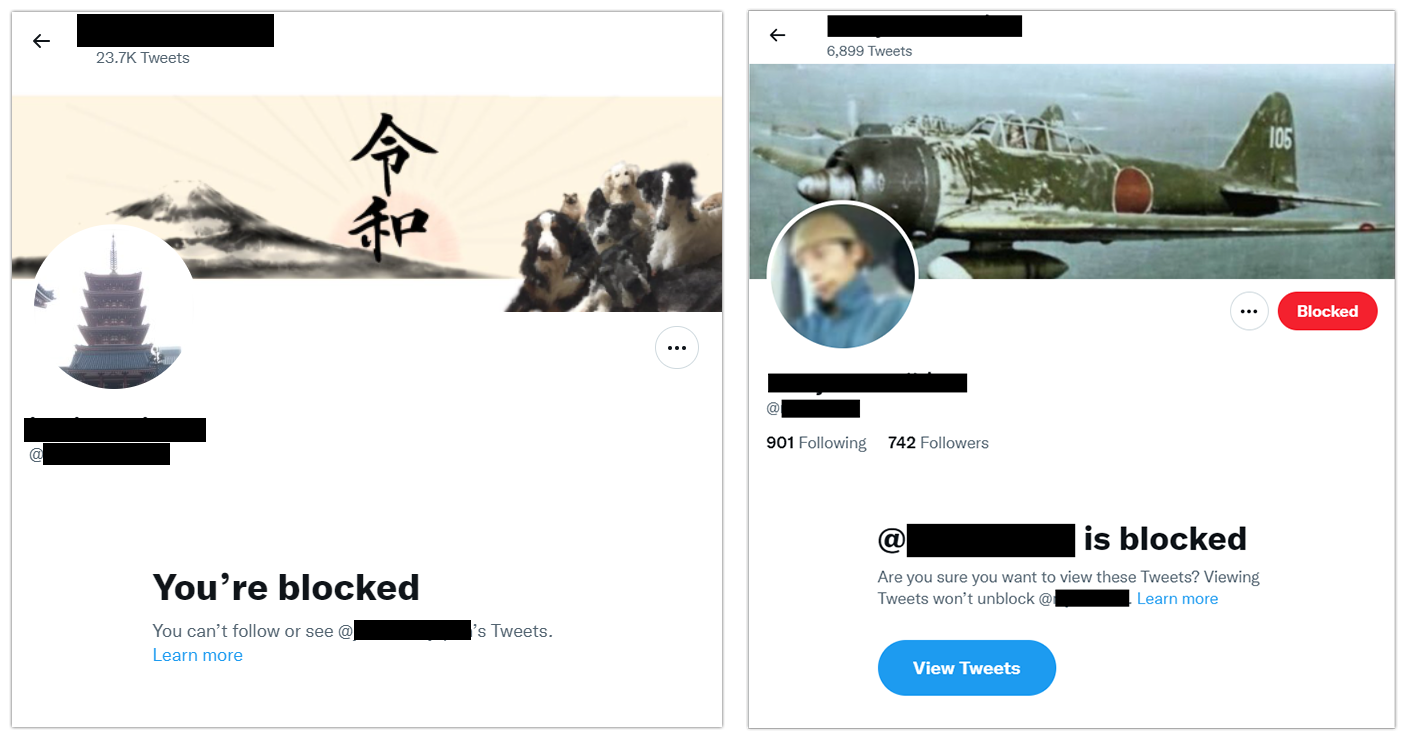

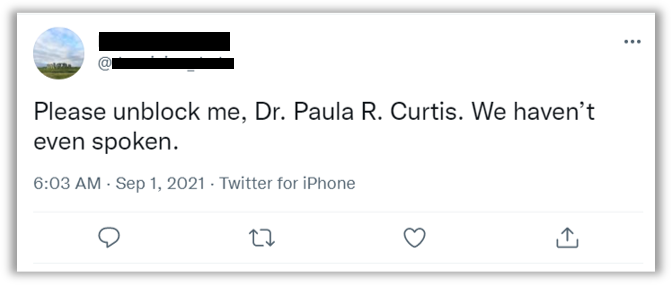

A hard block is the next step. This prevents someone from viewing your account and viewing your tweets when they appear in someone else’s timeline or thread. Again, users are not notified, but if they visit your profile, they will see that you have blocked them. In the screencaps below you can see an example of being blocked by someone (left) and blocking someone (right). As the image on the left shows, being blocked eliminates the ability to see that person's tweets from your account. On the right, note that even if you have blocked someone, if it is not mutual, you can still choose to see their tweets.

» Mass Block

For those of us who experience large-scale online harassment from particularly determined individuals or communities, the ability to mass block a large number of bad actors at once is essential. This is something you can do preemptively if you know there are certain bodies of users that you will never want to have looking at or reproducing your content or if you find yourself targeted and need to respond after the fact. Here I will briefly introduce the functionality of three tools I have found particularly useful.

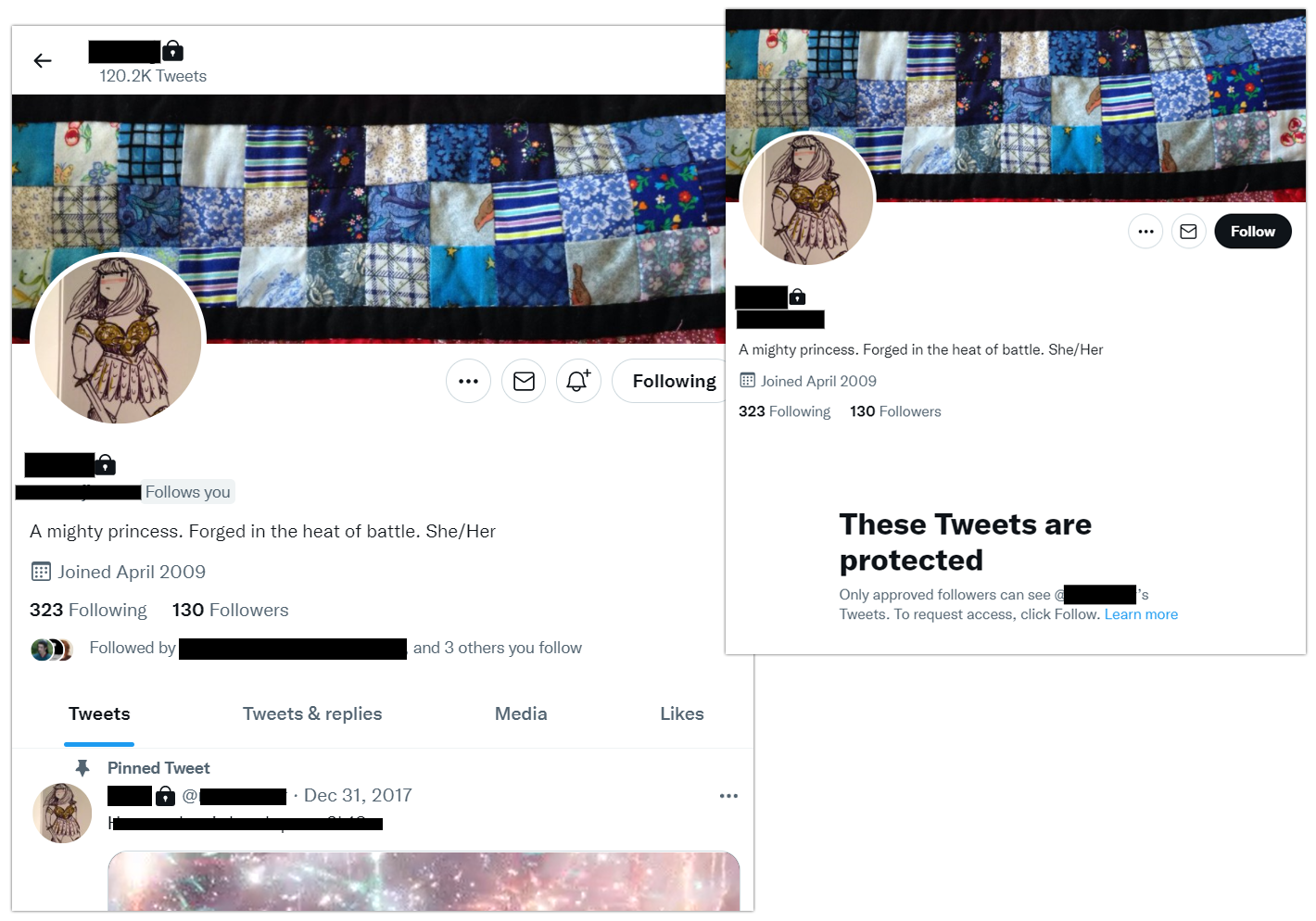

» Private Account

Finally, the most extreme option you have is to completely lock down your account and make it private. Note the little lock symbol next to the username below. On the left, you can see what a private account looks like for someone who is a follower (tweets are visible) and on the right, the account displays as locked down and inaccessible to a non-follower.

Doxxing

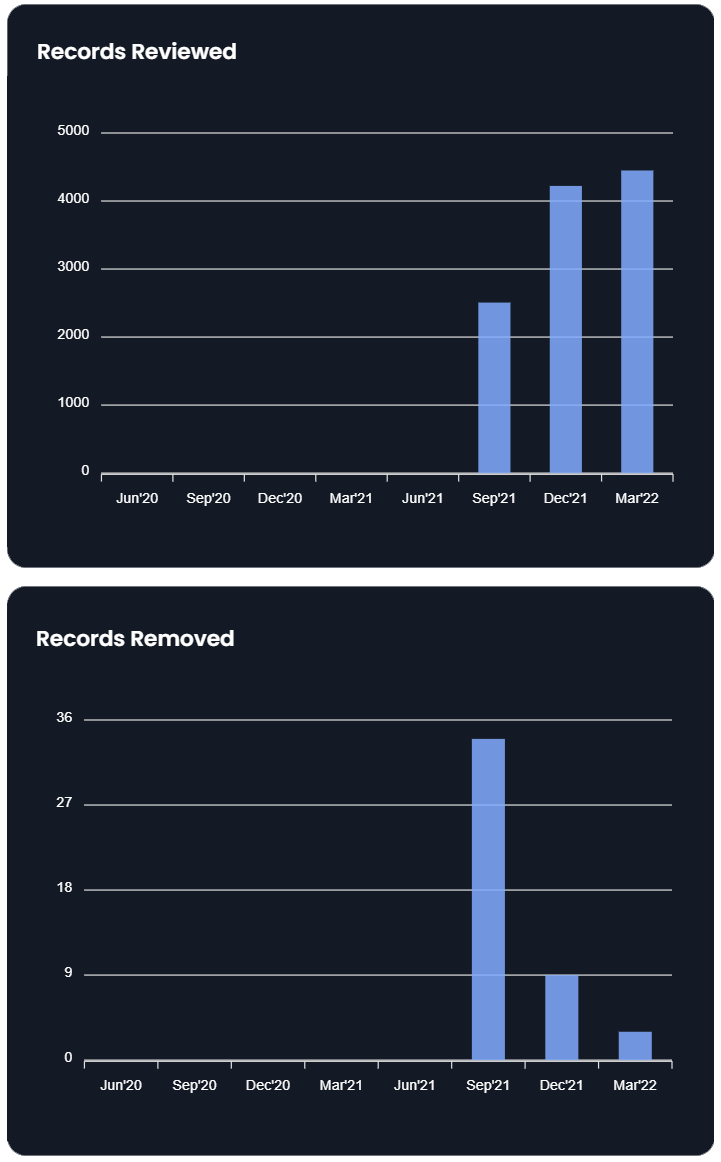

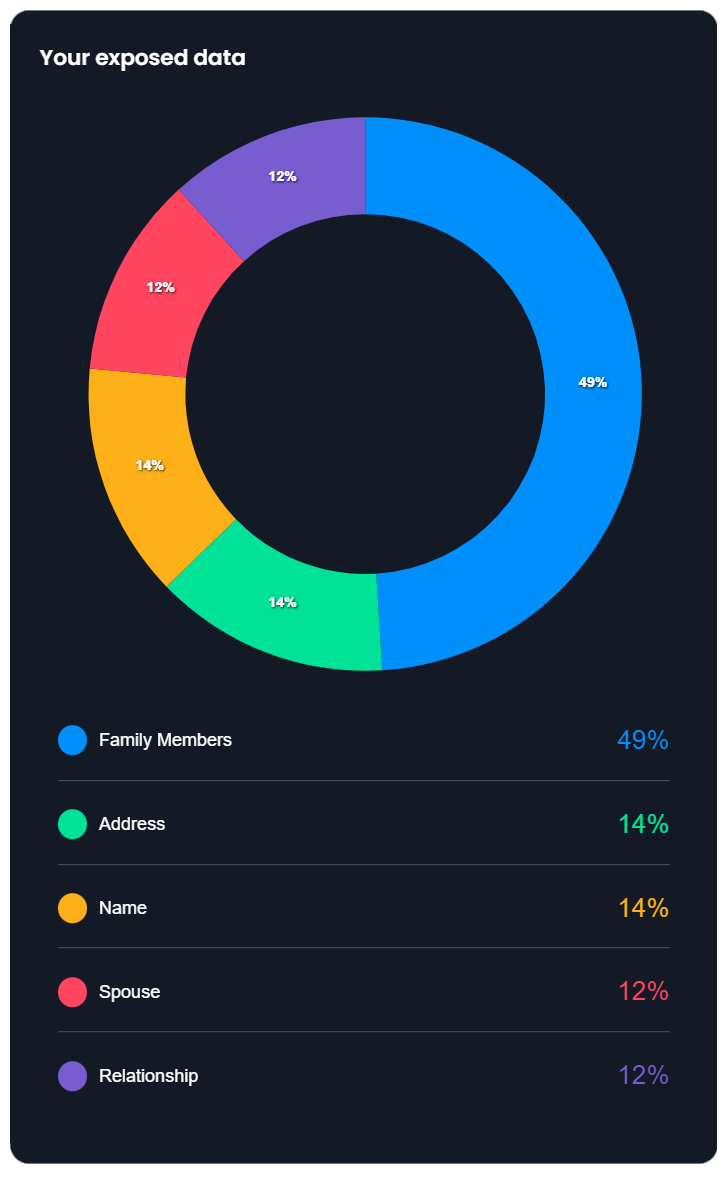

If your (successful) solution to someone bothering you is just a simple block or an account lockdown then you are one of the lucky ones. At its extremes, social media-based harassment can range from a stranger's stupid comment that is easily ignored to real world danger that can threaten careers and lives. It is therefore worth briefly discussing one of the most extreme forms of digital harassment, doxxing, which is a form of attack intended to spill over from online spaces into analog ones. If you are not already familiar, doxxing is a form of online harassment in which someone publicly reveals previously private personal information about an individual or organization. This could be your real name, your home address, where you work, or something else. In contrast to complaints you might read online, doxxing is not simply calling someone out who is otherwise already visible, tagging them in a post, or otherwise calling attention to them. At its most mild, doxxing could be something like sharing your private email address to a community of trolls. At its most severe, it can include using private information like a home or work address for a targeted attack like “swatting." Swatting refers to using someone’s location to call in a false police report in order to put an individual, their family, or others around them in a violent and potentially deadly situation under false pretenses. One of the most frightening parts of this kind of threat is that our personal information is actually not that difficult to find. By searching your name and other identifying information it is fairly easy to locate current or past addresses, phone numbers, relatives, and more. This information may also be shared through sites who profit from its redistribution known as data brokers.

- DeleteMe (for deleting public records)

- OneRep (for deleting public records)

- AccountKiller (for deleting your profiles/information from sites that make it difficult)

Putting Yourself First

Now that you’ve learned all of the horrible ways that things can go wrong and people are terrible, let me reiterate an important reminder in all of this: You Must Put Yourself First. Many of us perceive social media engagement as an all-encompassing thing. Something that sucks up all our time, that we must be constantly pushing content to, and that we have to persistently keep up with. But the right level of engagement for you is the right level of engagement. You control the platform, the platform does not control you. As this article has shown, there are ways for you to shape your experience to make it a healthier and safer space for you. Personally, I don’t follow any politicians or actors and extremely few news sites. The 24-hour clickbait news cycle frustrates and depresses me. And when I just can’t hear another hot take on COVID or pandemic life, I will mute the words “COVID” “pandemic” “virus” and “antivax” for 7 days, just to give myself a mental break. When I see someone I think is a weirdo or a bot, I remove or block them. If someone is harassing you or saying inappropriate things on your feed, get rid of them. You don’t owe someone yelling at you on the internet your time any more than you might owe an unhinged stranger a conversation if they approach you on the street. You also don’t have to be on social media all the time. If you want to not use it for a week, don’t. If you only want it on your computer and not your phone to resist the urge to check it frequently, take the app off. Want to only use your social media account on the weekend? Once a day? While at conferences? Sure! Who says you have to do otherwise? The important thing is that your mental wellness and well-being come first. Twitter’s feelings aren’t going to be hurt. You are the priority and the platform is your tool.Not All of Social Media is a Dumpster Fire

Having thoroughly scared you with all the possibilities of how things could go wrong, I think it’s also necessary to highlight that not all of social media is a dumpster fire. Seriously. For me, using Twitter has been an invaluable way to network with communities of scholars (and others) in Asian Studies, Medieval Studies, Digital Humanities, and more. It’s kept me up to date with the latest publications and research and shown me the fascinating tools that people use in their work and their teaching. Because I’ve been present, visible, and active, people who might otherwise not have known about my work have reached out to invite me to conferences, to write for edited volumes and magazines, or to teach classes or workshops. Because I share job data on East Asian Studies weekly, I’ve had non-profits related to Asian Studies reach out and ask me to speak to their representatives about my work. When I’ve gotten publicly cranky about errors in news articles, I’ve been asked by chief editors to speak with their writers and correct historical mistakes they've made. All of this has been a great way to gain experience in public engagement, forms of digital literacy, and where they intersect. Crucially, being present on social media has allowed me to learn from my colleagues who are facing similar (and very different) challenges in their academic work and careers. It has enabled me to be in solidarity with them and also to be a strategic advocate in public spaces, whether it’s for students, faculty, departments, or the field at large. Being online and engaged comes with great visibility. As we’ve seen, there are dangers to that, but we should not forget the possibilities as well. This article may reflect the darker corners of Twitter, but on the whole, I’ve had wonderful experiences using social media as a part of my professional development and I encourage people to consider how it may or may not be useful to them. If you’re wondering how to effectively use Twitter while giving your colleagues proper credit, creating content, and expanding your networks, I have written "A Guide to Best Twitter Practices for Academics (and Everyone Else)," which outlines some good strategies. On the topic of digital harassment and its impact on scholars of Asian Studies, you can also refer to a bibliography of suggested readings from our first Academics Online session. Be safe, and happy tweeting!3If you found this page or any other projects and public-facing writing on my site useful, please consider regularly supporting me via Patreon

. Writing and coding this information takes hours (and lots of hair pulling over broken code!). There is a lot of invisible labor that goes into it, which I do in my spare time. Support from the community I do this for means a lot to me and helps keep this site running. 🙂 Thanks for reading!

Last updated 2022.05.20

Images from iconmonstr and Irasutoya.

. Writing and coding this information takes hours (and lots of hair pulling over broken code!). There is a lot of invisible labor that goes into it, which I do in my spare time. Support from the community I do this for means a lot to me and helps keep this site running. 🙂 Thanks for reading!

Last updated 2022.05.20

Images from iconmonstr and Irasutoya.

-

An earlier version of this article also appeared in Critical Asian Studies, October 12, 2021. ↩

-

It is also worth noting that Facebook purchased Instagram in 2012. ↩

-

A special thank you to Tristan Grunow for editorial assistance on this page! ↩